|

|

| |

|

September 2024

|

Sibling Showdown: How One Missing Word in a Will Divided a Family

|

|

“From small mistakes come great catastrophes.” (Justin Cronin)

We’ve all seen how even the smallest mistake can have huge consequences down the line. A recent High Court spat between siblings over a poorly-drafted will confirms once again that when it comes to important documents (and it doesn’t get more important than your will!), every word counts.

The joint will and the “30-day survivor” clause

In their joint will, a wealthy couple had left everything to each other. When the husband died, his wife inherited their whole joint estate. Things started to come unstuck when she was then found to be unable to manage her own affairs and placed under curatorship – before she had a chance to make her own new will.

When she died 3 years later, only the original joint will remained. Her three children quickly came to blows over whether that joint will still applied to their mother’s estate, or whether she had died without any will (“intestate”).

- At issue was a “30-day survivor” clause in the joint will reading (as translated from the original Afrikaans): "Only if we die simultaneously or within 30 (thirty) days of each other, in such circumstances in which the survivor does not make a further will, then in that case we will bequeath the entirety of our estate as follows...".

- Did that wording mean that the joint will no longer applied? For the children, that was a critical question, because in their joint will the couple had left the lion’s share of their estate (a property and the family businesses) to the son. No doubt that was because he had played a “central role” in the management and funding of the businesses. But it left his two sisters to inherit only the “residue” of the estate – clearly an unattractive proposition to them.

Unsurprisingly, the son, hoping to keep his “lion’s share” of the estate, argued that the joint will was still valid and applied to his mother’s estate. Equally unsurprisingly, his sisters, hoping for a three-way split of the total estate, argued the opposite – that the joint will had fallen away and that their mother had died intestate.

“And” or “Or”? One missing word, a world of difference

As is all too common when sibling heirs fall out over the “who gets what” aspect of their parents’ passing, swords were drawn, and the High Court had to adjudicate.

The Court found itself having to decide between two possibilities. Had the couple meant to say:

- “Only if we die simultaneously or within 30 (thirty) days of each other, or in such circumstances in which the survivor does not make a further will…”. That “or” would mean that the joint will was still valid, and the son would get his lion’s share;

OR

- “Only if we die simultaneously or within 30 (thirty) days of each other, and in such circumstances in which the survivor does not make a further will…”. That “and” would mean that the joint will no longer applied, that the mother had died intestate, and that the estate would be split three-ways.

The Court described the will in question as “an inelegant and very badly drafted document.” But it also noted that a will is “held void for uncertainty only when it is impossible to put a meaning on it” and that “any document must be read to make sense rather than nonsense.”

The Court decided that it could make sense of the sentence in question and duly held that the couple must have intended their joint will to survive if the surviving spouse did not subsequently make their own new will.

The end result – the joint will stands and the son “wins”. But of course, all three siblings are “losers” when you consider all the familial conflict, angst, time-wasting and costs that surely accompanied this litigation.

Avoid all that uncertainty and family conflict

No one wants their loved ones fighting over their estate after they are gone. But as this unhappy case so clearly shows, even the slightest inelegancy in wording can lead to just that. Let us help you draft a will that is clear, concise and fully reflective of your last wishes.

|

|

When Can You Legally Record Conversations?

|

|

“Big Brother is watching you.” (George Orwell)

Your smartphone lets you record just about anything, anywhere, and at any time. Your laptop and other devices can automatically record online meetings. Technology enabling voice and/or video recording is all-pervasive, providing us all with a powerful tool for keeping accurate records, resolving disputes and gathering evidence.

But it’s crucial to understand when it’s legal to start recording – and when it’s not… Whether you’re talking face-to-face, over the phone, or via digital platforms like WhatsApp, Zoom, Slack, or Teams.

The law: What’s allowed & what’s not

The legal framework for recording conversations in South Africa is primarily governed by the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA). The Act is aimed not only at regulating “Big Brother” type government surveillance of its citizens, but also at protecting us from each other when it comes to our rights to privacy generally.

Also relevant is the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) which regulates the processing of personal information. Its impact on recording conversations relates primarily to how the recorded information is handled, stored, and shared.

Here are some key points to consider:

- Recording conversations you aren’t party to: Recording conversations between other people, to which you are not a party, is generally illegal unless explicit consent is obtained from all parties. That’s because RICA has a general prohibition against “intercepting communications” without the knowledge and consent of those involved. There are only very limited situations where such recordings may be legal, such as under a court order or for establishing a person’s location in an emergency rescue situation.

- Recording your own conversations: If, however you are directly involved in the conversation, you are legally allowed to record it without consent. RICA permits individuals to record communications to which they are a party, either as a direct participant or in their “immediate presence” and within audible range. There is no legal obligation on you to inform or obtain consent from the other participants before recording, but, as we discuss below, there are often good practical reasons for doing so anyway.

Note that specific rules apply to recordings “in connection with carrying on of business”. To comply with POPIA ensure that you have a clear, lawful purpose for your recording, and that you use it only for that purpose.

- Recording public conversations: In public spaces, where there is generally no expectation of privacy, recording conversations without consent is unlikely to land you in serious trouble but be careful what you use your recordings for. For example, a person’s image, voice, preferences or opinions is “personal information” subject to POPIA’s restrictions on its use and storage. Moreover, always consider the context before recording as there may be situations where privacy is reasonably expected.

What about workplace communications?

As an employer, you may need to record calls and workplaces for security, compliance, or training purposes, but tread carefully here as clear and transparent communication is essential to maintain trust and to avoid dispute.

You should typically inform your employees if their communications or workplace activities are being or could be recorded. This can be done through employment contracts, policies, or direct notification. As always with our employment laws there is no room for error, so specific advice is essential!

Practical tips for recording conversations legally

If you plan to record a conversation, consider these practical guidelines to ensure you stay within legal boundaries:

- Informing others: Even when it might not be legally necessary, informing the other parties involved that you are recording can help prevent misunderstandings and build trust. Many platforms like Teams and Zoom will by default advise all meeting participants upfront that they are being recorded. But there’s no harm in mentioning it specifically when you open the meeting, with an offer to share the recording with participants on request.

Particularly if you think your recording might be important in a legal dispute down the line (to prove the terms of an online contract for example), advising participants upfront of your intention to record can boost its value as evidence and make it difficult for an opponent to challenge it in court.

If your conversation is an international one, bear in mind that some jurisdictions have more stringent rules than others on the necessity for consent.

If in doubt, take no chances: The safest course of action will always be to ask for consent.

- Secure storage: Store recordings securely, especially if they contain sensitive information. POPIA requires that personal information be secure from unauthorised access or breaches, and that it be kept only as long as necessary for the purpose for which it was recorded.

- Responsible use: Be mindful of how you use the recordings. Sharing or publishing recorded conversations without consent can have serious legal consequences.

There are plenty of grey areas here, so please call us if you’re in any doubt.

|

|

Waiving the Bond Clause to Keep a Sale Alive: Risk Versus Reward

|

|

“This sale agreement is no more! It has ceased to be! This is an EX-sale!” (With apologies to Monty Python)

A “bond clause” – standard in most property sale agreements – typically provides that the whole sale depends on the buyer obtaining a mortgage bond by a specified date. If the deadline comes and goes without a bond being granted, the sale lapses and the buyer is entitled to get their deposit back.

Most agreements also provide that the bond clause is there for the sole benefit of the buyer, who is thus entitled to waive it, i.e. to tell the seller “I no longer need a bond and I’ll pay the purchase price in cash so the sale can proceed.”

There’s both risk and reward in that

The rewards in such a situation are obvious – both buyer and seller benefit from the sale going through.

But there’s also a risk factor if the “waiver” is open to doubt, as a recent SCA (Supreme Court of Appeal) fight illustrates.

“The whole sale agreement has lapsed, I want my R1m deposit back”

Just before the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown struck and disrupted everything (with a Deeds Office closure to top it all), the buyer bought a house for his daughter and her family for R4.95m. He paid a R1m deposit into a trust account and undertook to pay the balance on transfer. The sale agreement included a standard bond clause, worded along the lines set out above.

The buyer applied for a bond and was eventually granted one. But, critically, this only happened after expiry of the deadline set out in the bond clause. Meanwhile – and here we come to the nub of this dispute – a conveyancing secretary wrote an email advising that “…we have spoken to the purchaser and the purchaser advised that he will make payment of the full purchase price… He will be buying the property cash.” That “waiver email”, the seller would later argue, was the buyer waiving the benefit of the bond clause through the agency of the conveyancer.

- Many delays and emails later – caused largely it seems by the lockdown – the daughter and her family were given early occupation as they were keen to get going with repairs, alterations and landscaping. That happy process all came to a screeching halt when an architect discovered that there were no plans for parts of the building and that it was thus illegal. The daughter returned the keys, and her father demanded a refund of his deposit.

- The seller refused, claiming that the buyer had both waived his right to rely on the bond clause and repudiated (renounced) the sale. His deposit would therefore be retained to cover the seller’s damages claim against him.

- The buyer retorted that he had never waived his rights under the bond clause, and that the whole sale was null and void from midnight on the date of expiry of the bond clause deadline. That, argued the buyer, entitled him to the return of his R1m deposit.

Waiver and the law

Battle lines drawn, the first round went to the buyer: the High Court agreed that the sale had lapsed and ordered that he be repaid his R1m.

Round two was no better for the seller. The SCA, refusing his application to appeal against the repayment order, held that there is a factual presumption against waiver in our law. The onus was therefore on the seller to prove that the buyer had waived his rights to the bond clause. He needed to provide “clear proof” of a “valid and unequivocal waiver” showing that “[the buyer] was aware of those rights, intended to waive them and did do so”. The Court said he had failed to prove this.

Moreover, the agreement required (as is standard) “that any waiver of any right arising from or in connection to the agreement be in writing and signed by the party to the agreement.” No proof of that here, held the Court. And when it came to the seller’s suggestion that the conveyancer had acted as the buyer’s agent in writing the disputed “waiver” email, the Court held that the seller had failed to prove that the conveyancer “was duly authorised to waive those rights, of which [the buyer] was fully aware, and that [the conveyancer] knew all the relevant facts, was aware of those rights and intended to waive them.”

The end result: There was no need to argue over the lack of building plans. The sale died when the bond clause deadline expired. It was, as Monty Python might have put it, deceased, expired, and bereft of life. The buyer gets his R1m back.

Remember: A lot is at stake in property sales, and it’s easy to put a foot wrong. Speak to us before you sign anything!

|

|

Divorce and the New Three-Pot System: Another Risk To Manage

|

|

“Divorce is the one human tragedy that reduces everything to cash.” (Rita Mae Brown)

How will the new “Three-Pot Retirement System” (often referred to as a “Two-Pot System”) affect financial arrangements on divorce? Retirement savings can amount to a significant portion of a marriage’s assets, so it’s important to understand the implications of the new system.

First, a quick refresher

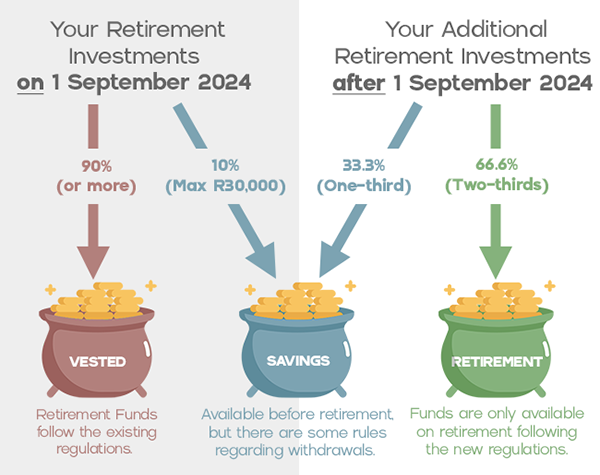

Have a look at our graphic below for a neat summary of the three “pots” and what they’re all about.

- The “Vested Pot”: This will hold most of your existing (as at 1 September 2024) retirement investments, and the current regulations continue to apply.

- The “Savings Pot”: You will be able to withdraw funds from this pot before you retire. Rules apply and you should avoid depleting this pot except in real need.

- The “Retirement Pot”: You will (with only a few limited exceptions) only have access to these funds when you reach retirement age (usually 55, depending on the fund).

What happens to these three pots on divorce?

This is of course a brand-new system, and there have been concerns raised about a number of grey areas that may arise in a divorce context. Only time will tell if these will have any meaningful practical effect on divorcing spouses. These exceptions aside, the overriding sentiment seems to be that not much will change other than that your marriage’s “pension interests” will be made up of three distinct pots, rather than just the current one pot.

As such, all three pots will be dealt with as follows:

- If you are married in community of property, they will be divided equally between you.

- If you are married out of community of property with the accrual system, they will fall into the accrual calculations unless you expressly excluded them in your ante-nuptial contract.

- If you are married out of community of property without the accrual system, they might still be taken into account if the court orders an asset redistribution.

And remember, you can always agree between yourselves on a different split upfront in your ante-nuptial contract or on divorce in a settlement agreement.

One new risk to manage

Until now, there has been no “Savings Pot” for a member spouse to potentially deplete as soon as the possibility of divorce raises its ugly head.

While we all know that families should never risk missing their retirement goals by dipping into their long-term savings in any but genuine emergencies, it goes without saying that an acrimonious divorce could quickly change the focus from “let’s save for the future” to “grab it while you can”.

If the worst happens and your marriage hits the skids, be aware that the new legislation states that only when pension funds are given formal written notice, with proof, of divorce proceedings or pending asset divisions, are they legally prohibited from allowing a withdrawal (or granting a loan or guarantee) without your consent as the non-member. That formal prohibition lasts until the divorce is finalised or a court order is issued.

Some have suggested that even before you get to that formal stage, you should alert the pension fund administrators that they should assess any withdrawal requests in light of possible future divorce claims. How that will actually play out in practice remains to be seen, but it is worth noting.

The new system is a lot to get your head around and it’s natural to have questions. Don’t hesitate to ask us for help!

|

|

Legal Speak Made Easy

|

|

“Bona fide”

An important and commonly encountered legal concept, the Latin phrase “bona fide” translates to “in good faith”, implying an absence of fraud or deceit. Its opposite is “mala fide” or “in bad faith”. A fundamental concept in law since ancient Roman times, it’s still used in legal systems around the world two millennia later!

In South Africa it remains ubiquitous in our court decisions and legislation. Whether or not something is found to be “bona fide” can often make or break the outcome of litigation.

|

|

Note: Copyright in this publication and its contents vests in DotNews - see copyright notice below.

|

| |

|

|

|

|